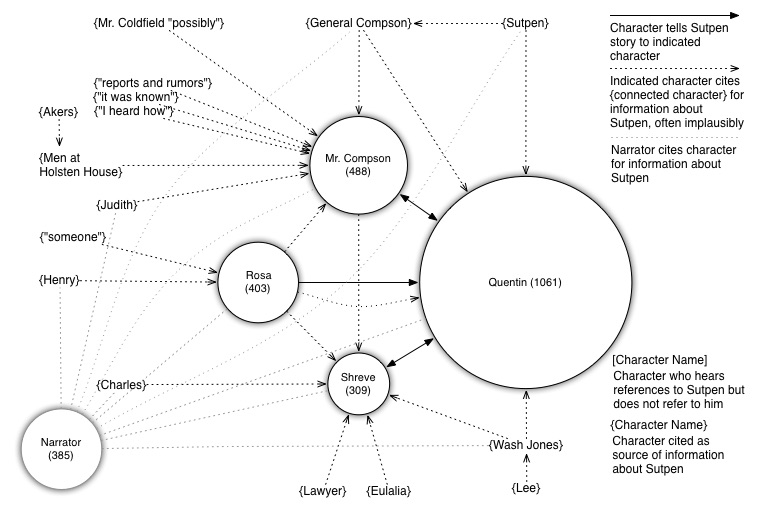

The Sutpen storytelling network in Absalom, Absalom!, representing narrators who refer to Sutpen, and their named

sources of information about him (however implausible).

The Sutpen storytelling network in Absalom, Absalom!, representing narrators who refer to Sutpen, and their named

sources of information about him (however implausible).

While thinking about how this structure is different from a more traditional (pre-modernist) novel (like Flags in the Dust for instance) I travelled to Faulkner's hometown of Oxford, MS, to research what was happening in the city at the time Faulkner was writing portions of this novel. It turns out that the summer of 1935 saw a heated debate over the supply of electricity in the city. The city itself had been generating power for decades, but the new TVA was coming into small southern towns and taking over production and distribution. I saw this more distributed model of energy networks as a metaphor for Faulkner's more distributed model of narrative and storytelling in Absalom, Absalom! Here's the opening paragraph of the essay:

Electricity was in the air in Oxford, Mississippi in the months of 1935 and 1936, when Faulkner was writing and revising chapters of Absalom, Absalom! and mailing them off to his editor, Hal Smith. Absalom’s narrator describes Quentin feeling “exactly like an electric bulb” (143) as he sits next to Rosa on their way to meet Henry at Sutpen’s Hundred. Quentin remembers his father describing youth, the “young and supple and strong” who can react “as instantaneous and complete and unthinking as the snapping on and off of electricity” (218). Shreve imagines Sutpen telling Henry that Charles is his brother and Henry calling his father a liar “that quick: no space, no interval, no nothing between like when you press the button and get light in the room” (235). Earlier in the novel, referring to Sutpen’s three-year hiatus, the narrator describes him as “completely static, as if he were run by electricity and someone had come along and removed, dismantled the wiring or the dynamo” (31-32). And let’s not forget Rosa’s understanding that “the cost of electricity was not in the actual time the light burned but in the retroactive overcoming of primary inertia when the switch was snapped: that that was what showed on the meter” (70). Taken together, these references are surprisingly anachronistic for a novel whose primary events take place long before the first municipalities began lighting their streets. They provide evidence for the argument that language, especially novelistic language as described by Mikhail Bakhtin, is shaped by culture, discourse, and technology. Faulkner worked in the Ole Miss power plant in 1929 and perhaps was influenced linguistically from that experience. But the discourse on electricity in Oxford, MS in 1935-36, during the months that Faulkner was writing and revising Absalom, Absalom!, did much more to shape both the language and the storytelling structure of this novel.

You can find Faulkner in Context at Amazon.

Header image is from Faulkner's 1936 drawing of his fictional Yoknapatawpha County and can be found widely on the internet.